As we discussed in our earlier post, as Iowa City grew in the mid-1800’s, so did the brewing business. Much like today, hard-working Iowa Citians enjoyed the refreshment found in a mug or two of freshly-brewed beer. And by 1880, there were three major breweries located on Iowa City’s north end that produced enough barrels to satisfy the growing population of Johnson County.

Interestingly enough, these three breweries, while hiring hundreds of employees, were at their core, family-run businesses created by a small handful of German-American pioneers who took their passion and expertise in brewing and turned it into a highly-profitable financial empire that some called the Iowa City German Beer Mafia. Allow me here to introduce you to the three kingpins…

1. Englert City Brewery (1853) – John J. Englert & Frank Rittenmeyer

2. Union Brewery (1857) – Conrad Graf

3. Great Western Brewery (1857) – John P. Dostal

While in competition with each other, the owners of these three major breweries all cooperated with one another in ways that kept the beer-brewing business in Iowa City a close-knit fraternity that defended itself against friend and foe alike.

Another common link that held the German Beer Mafia together was the unique tunnel system built between the three breweries on Market and Linn Streets. Built by hand before the days of refrigeration, these amazing tunnels, constructed 30 feet below street level, were a perfect place to store inventory, keeping beer cool during the hot summers of Iowa City.

Without a doubt, the biggest on-going threat to Iowa City’s German Beer Mafia was the push for prohibition – making the sale of alcoholic beverages illegal.

While most know about the huge prohibition battle across America in the 1920’s, fewer know that the people of Iowa actually struggled with this issue long before it ever came onto the national stage.

In 1847, for example, only months after Iowa statehood, the Iowa State Legislature passed a law that restricted the sale of alcohol by limiting the number of liquor licenses granted in a township. In 1851, “dram shops” (bars) were prohibited statewide, but many retailers navigated around that law by opening taverns that combined food and housing options alongside the sale of liquor. In 1855, an outright ban on alcohol was put into place but the law included a local option, allowing Iowa’s counties to decide whether or not they would be “dry.” Johnson County, during this time, chose to be a “wet” county, opening the door for the big expansion of breweries we discussed in our earlier post.

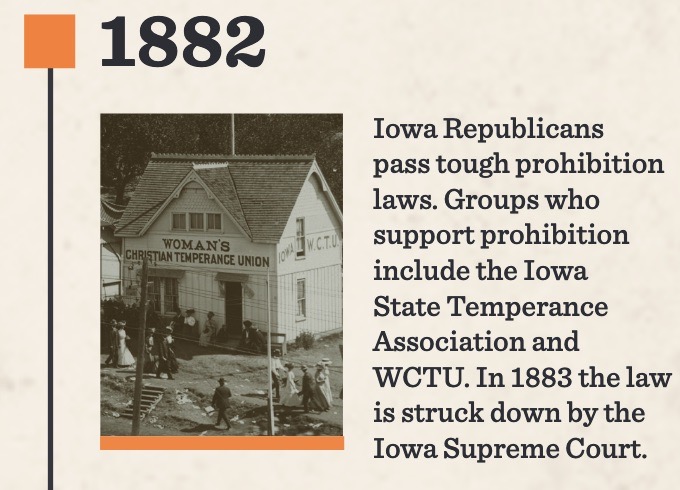

In June 1882 – The Republican-led Iowa State Legislature passed the Iowa Liquor Prohibition Amendment, also known as Amendment 1, which then placed state-wide prohibition on the June ballot. 55% of the state’s voters approved the amendment (155,436 to 125,677), prohibiting the sale, manufacture and consumption of alcohol. Opponents to the amendment were furious and seeing some under-handedness in the legal process, took the voters’ decision to court.

In April 1883 – The Iowa Supreme Court upheld the argument of the opposition, and because of irregularities surrounding the process used in submitting the vote to electors, the amendment was found unconstitutional. Chalk up one for the pro-beer drinkers.

In February 1884 – In response to the 1883 decision by the Iowa Supreme Court, the conservative-minded Iowa State Legislature countered, passing a new law that brought back prohibition. But in order to pass the bill, the moderates in Des Moines insisted for a “local option,” giving each of Iowa’s 99 counties the final say on how the new prohibition law, which would go into effect on July 4, 1884, would be enacted. This move actually returned Iowa to the way things were in 1855, but now, in Iowa City, many of the city leaders were now Republicans who wanted our city to be “dry.” This locally-based decision for prohibition infuriated many, especially the German Beer Mafia and its large base of employees.

July 4, 1884 – On the day the new prohibition law was to take effect in Johnson County, Iowa City brewer (and good German Democrat) Conrad Graf decided to protest by throwing a beer party at his place of business (Union Brewery). Since the sale of beer was now prohibited, he decided to offer his product free of charge. As you might imagine, with tensions already running high, quite a few people lined up outside Union Brewery as Graf tapped his first keg. As lines piled up, and waits for a mug of beer reached half an hour or more, the agitated townsfolk became a bit rowdy. This, of course, drew in the police, who by order of the city attorneys, locked the bar, making the crowd all the more persistent. Soon, the crowd was throwing empty kegs through the windows in order to enter the building. Discovering more beer locked in the cellars, they forced their way in, and in the end, managed to drink every last drop of Graf’s beer. Within days of Conrad Graf’s “beer party,” all three owners of the German Beer Mafia – Graf, John J. Englert (City Brewery), and John P. Dostal (Great Western Brewing) – were given written warnings from the Johnson County sheriff stating that by continuing to distribute beer in Iowa City, they were breaking the new prohibition law. In their rage, Graf and Dostal tore up the papers, forcing the sheriff to immediately issue a citation for their arrest.

In response, the determined business men sent a warning to the city (above) and began to plan their next move – one that would hopefully strike fear in the hearts of Republican prohibitionists, and in the process, get city officials off their backs. The plan was truly monstrous and was set for August 13, the day before Graf and Dostal were scheduled to go on trial. According to local historians, the plan included 1) assembling a large crowd at the home of Justice John W. Schell, 2) capturing and lynching city attorneys John and L. G. Swafford, the alleged informants/witnesses for the prosecution, and 3) the tarring of the county lawyers who were prosecuting their case on August 14.

August 13, 1894 – When the day arrived, Graf, Englert, Dostal, and a mob of at least 150 brewery workers marched to Judge Schell’s farm home, located east of town in Scott Township. Once there, the mob, armed with ropes and tar, surrounded it, ready to act. When A.E. Maine, the city prosecutor who had gathered with other Republican leaders earlier at Schell’s home, attempted to deliver legal briefs to Graf and Dostal, he was kicked to the ground, stripped bare, and tarred by the mob. At that point, a city policeman named Parrott, a county deputy named Fairall, and Judge Schell all came to Maine’s aid, helping him back into the house. Reports indicate that Parrott was stabbed in the leg and Schell pummeled in the process.

At that point, the rioters began throwing stones at the house and apparently some even pulled out their revolvers, shooting randomly at the home. These actions terrified Schell’s wife and children, and Mrs. Schell then stepped out on the front porch imploring the mob to desist as her mother, who was also inside, was on her deathbed. That seemed to quiet the crowd temporarily, until J.J. Englert yelled out that he would burn the house down unless the men inside surrendered. Fairall, in response, cried out that he would shoot the first man who broke the door in. Graf yelled back, “You will shoot, will you? Damn you – shoot!” This standoff went on for hours before finally, at dusk, the angry mob decided to move their demonstration back into the city, gathering in City Park, which at the time was directly across Jefferson Street from St. Mary’s Church. There, they continued their tirade into the wee hours of the night.

Late in the evening, in City Park, Conrad Graf spotted the alleged informants (John and L. G. Swafford). In his anger and with the help of some 30 rioters, Graf assaulted the two men, tarring the brothers and beating them to a bloody pulp. Reports of the incident indicate that the Swaffords were saved from a hanging when nearby citizens intervened and carried the two brothers safely away, housing them for their own protection, in the county jail.

As you might expect, the August 13th riot gained much national attention, and while much ink was spilled, city officials were reluctant to make any further arrests since any new action on their part could easily arouse more trouble in a city that was already torn down the middle when it came to determining who was in the right and who was in the wrong. To make matters worse, John J. Englert, one of the defendants in the case, sat on the Iowa City city council!

“Not since the murder of Boyd Wilkinson has Iowa City been thrown into such an excitement as prevailed yesterday afternoon and last night, and that is still prevailing today.”

After a few weeks of high tension, Johnson County officials finally decided to issue arrest warrants for Graf, Englert and Dostal, but by that time. the three brewers simply couldn’t be located. For their egregious injuries, the Swafford brothers sued Graf for $20,000, but a deeply-divided grand jury in Iowa City refused to make any indictments, causing the trial to move to Marengo, and finally Marion in Linn County, in order to reach a settlement for $7,000 (the equivalent of $164,000 today). According to the records, the unabashed brewers shared that cost, paid up, and moved on.

After all this summer hullabaloo in Iowa City, things died down a bit. While the Iowa state law didn’t change, local city officials did – resulting in a more moderate stance in Johnson County about alcohol production between 1884 and 1916. While prohibition-loyalists did ultimately get their way after the turn of the century, the Republican Party in Iowa took some severe hits for their heavy-handed approach to the alcohol issue. Much has been written about the pros and cons of America’s futile attempt to legislate morality, so I’ll save my personal thoughts for later writings. Suffice to say that some of the decision to give more grace to the German-Democrat beer-makers after the riots might have been based on the fact that two of the three main instigators of the uprising stepped away from their businesses around this same time.

John J. Englert – Seeing the prohibition hand-writing on the wall, the Englert family had already begun transitioning (1883) from their successful beer business to selling two even more lucrative products – firewood and ice. While John J. Englert involved himself in the 1884 uprisings, his company, located at 319 E. Market, had already decided to move on, and within a few years, Englert’s sins were forgotten and, as you know, the Englert’s became one of Iowa City’s best-known families. Read more about the Englerts here.

John P. Dostal – Obviously a very short-tempered man, Dostal became disgusted with the entire situation, leaving town in a huff, moving first to Aurora, Illinois and then to Denver, Colorado, eventually taking his beer business with him. His sons, George and John, remained in Iowa City, attempting to keep Great Western afloat, but eventually sold it all to Fred W. Kemmerle, Dostal’s partner in Aurora, Illinois, who renamed the business The Iowa Brewing Company in 1902. The building, located at 332 E. Market, was suspiciously destroyed by fire in 1909.

Conrad Graf – A stubborn German-Democrat, Graf kept Union Brewery going, despite the on-going battle with his Republican prohibitionist counterparts. Eventually, Graf turned things over to his two sons, William & Otto, who renamed the business in 1903: Graf Brothers Brewery. The Grafs continued to operate as a brewery until 1916, when Iowa returned to full prohibition. At that point, the Grafs attempted to produce soda, but residual yeast spores caused the soft drink to ferment. Below, Iowa City historian Irving Weber tells us more…

As writer Marlin R. Ingalls concludes…

“Only Graf’s Union Brewery at 231 N. Linn Street (remains) to remind us of Iowa City’s period of prohibitionists, scofflaws, the German Beer Mafia and alcohol fueled civil disobedience.”

Might we all learn some excellent lessons from this volatile time in our city’s history, so we not repeat, in our day, such poor decisions that would lead to similar tragic events, or even worse. Here’s a raised glass of suds to peace, prosperity, and individual freedom!

Here’s a tip of the old hat to the many home-town breweries that have sprung up around Johnson County in recent years – continuing our rich Iowa City tradition of making great beers that rival the best. See a complete list here.

Kudos to the amazing resources below for the many quotes, photographs, etc. used on this page.

German-American Brewers in Iowa City, Glenn Ehrstine, GermaninIowa.files.wordpress.com

Iowa City Breweries, OldBreweries.com

Union Brewery (Iowa), Wikipedia

Timeline of Prohibition in Iowa, IowaCulture.gov

Iowa Liquor Prohibition, Amendment 1 (June 1882), Ballotpedia.org

The Iowa City Beer Riots of 1884, Marlin R. Ingalls, Little Village, March 26, 2013

Is this heaven? No, it’s beer, Claire Dietz, The Daily Iowan, September 21, 2016

1884, the year Iowa City rioted over beer, Claire Dietz, The Daily Iowan, September 13, 2017

Beer cave underneath the former Union Brewery of Iowa City, GermansinIowa.com, September 18, 2015

John Wilbur Schell, Find-A-Grave

John P. Dostal obit, Iowa City Press-Citizen, April 15, 1912, p 4

Click here to go on to the next section…

Click here for a complete INDEX of Our Iowa Heritage stories…